We walked into that pitch convinced we were presenting The Next Big Thing. We’d spent 18 months building. Had NDAs signed. A full agile team shipping features weekly. The investor—the only one in town—listened for 20 minutes and passed. That’s when we realized we’d been building in a vacuum.

The Idea That Seemed Brilliant

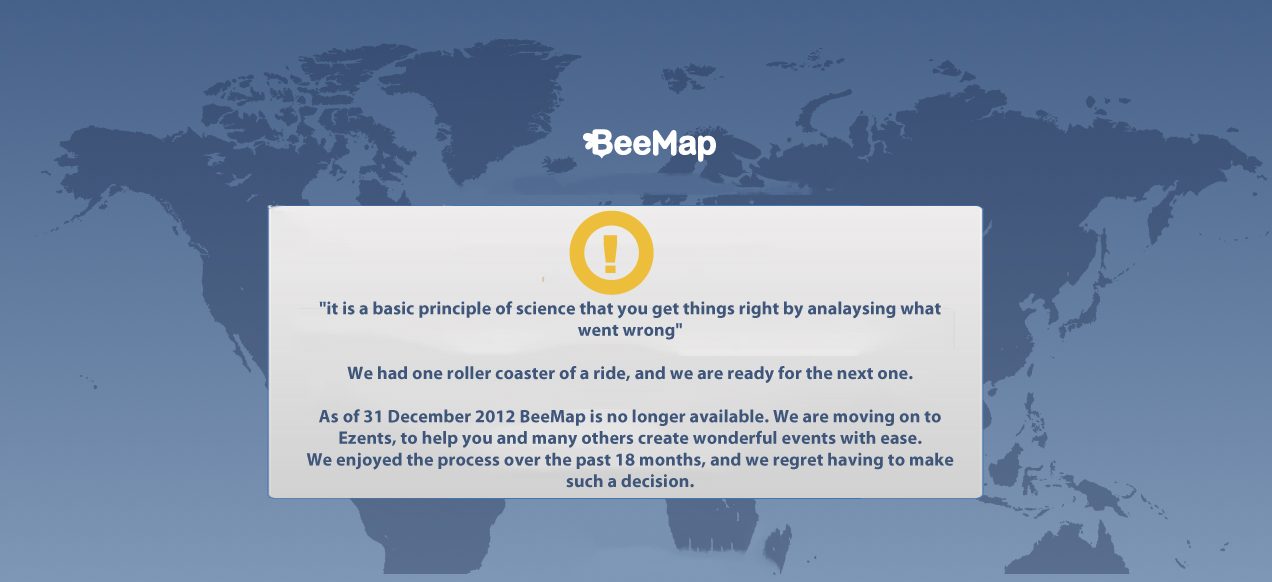

BeeMap was a location-based social network. Imagine Google Maps where every person on earth reserves their own spot. Now add social infrastructure on top—posts, messages, profiles, chat, connections. You’re a graphic designer in New York? Zoom in on the map, see every designer there, browse their work, interact, connect.

We even had a slogan: “The Next Big Thing.” We meant it.

The 18-Month Build

We started with a simple concept. Then we kept adding features.

Social feeds. Private messages. Walls. Live chat. Friends. Followers. Professional connections. Every sprint added something new. We moved from Google Maps to Mapbox to OpenStreetMaps as our needs evolved. The technical architecture grew more sophisticated.

We had four founders. Four developers. A team lead. A designer. QA. We were one of the first startups in the region running proper agile/scrum. Standups, sprints, retrospectives—the whole playbook.

Every two weeks, we shipped features. What we never shipped: learnings.

We were moving fast technically. We weren’t moving fast strategically.

The Vacuum

Here’s what we didn’t do during those 18 months: talk to anyone outside the team.

We were secretive. Everyone signed NDAs. We didn’t talk to potential users. We didn’t share mockups with our network. We didn’t pitch investors for feedback.

The logic seemed sound: build it first, then they’ll see the vision. Protect the idea. Execute in stealth. Launch with impact.

The reality: we were solving a problem we assumed existed. We never validated that assumption because we never asked.

Launch Day(s)

When we finally opened up, we invited our team and friends to sign up. We posted on other social networks. We ran this campaign for almost a month.

The metrics told a brutal story.

No real interest. Low signups. The few users who did join didn’t come back. They’d look around, post once maybe, then disappear. The engagement we’d built the entire platform around? It never materialized.

We had an investor pitch scheduled. This was supposed to be our validation moment—not for the money, but for the signal that we’d built something worth backing.

He passed. Politely, but definitively.

That’s when the reality hit. We weren’t holding back a secret weapon. We’d spent 18 months building something nobody wanted.

What We Got Wrong

We Built Before We Validated

The most expensive mistake: writing code before talking to customers.

We should have spent week one talking to 20 potential users. Week two building the smallest possible test—maybe just a landing page with mockups. Week three getting reactions.

Instead, we spent 18 months in the dark.

You can do customer discovery with a Google Form and a Figma prototype. We chose to do it with a full engineering team and a production app. One approach costs a weekend. The other costs 18 months.

We Tried to Build Too Big

Social networks have a cold start problem. They’re only valuable when other people are already there. You can’t be the first person at a party—there’s no party yet.

We needed critical mass to make BeeMap work. We had no ignition strategy.

The smart move would have been to start hyper-focused. All graphic designers in Ramallah. All developers in Amman. One city, one profession, manual onboarding. Build density first, expand later.

Instead, we built for “everyone, everywhere.” Which meant we built for no one.

Perfectionism Killed Speed

Every feature felt necessary. Every technical pivot felt justified. We were building the “right” way—proper architecture, clean code, agile process.

But perfect is slow. And slow is deadly when you haven’t validated your core assumptions.

Our agile process helped us ship features efficiently. It didn’t help us learn if anyone actually wanted what we were building.

Speed isn’t about typing code faster. It’s about learning faster. We optimized for the wrong thing.

The Non-Obvious Lessons

“Talk to customers” is the obvious takeaway. Every startup article says it. Most founders ignore it anyway. So did we.

But here’s the deeper lesson: secretiveness is a startup killer.

We made everyone sign NDAs. We protected the idea like it was the crown jewels. Ideas aren’t valuable—execution is. And execution requires feedback, iteration, and market validation. You can’t get any of that in stealth mode.

The NDA protected nothing. It just isolated us.

The second lesson: social products have unique cold-start problems. Building the technology is maybe 10% of the challenge. Getting the first 100, then 1,000, then 10,000 people to show up and stay active—that’s 90% of the work.

We spent 18 months on the 10%. We had no plan for the 90%.

What Happened Next

We shut down BeeMap and pivoted to a new idea—a B2B events platform called Ezents. That had its own lessons about geography and market fit, which I’ll write about separately.

Were we disappointed? Absolutely. Did it almost kill our drive to keep building companies? Almost.

But we learned more from BeeMap’s failure than we would have from moderate success with something smaller. The expensive part wasn’t the money we spent. It was the 18 months.

Eighteen months we could have spent building something people actually wanted. Or failing three times instead of once, and learning three times as much.

If I Could Go Back

If I could go back to day one of BeeMap, here’s what I’d do differently:

- Week 1: Talk to 100 potential users. Understand their problems. Validate that location-based professional networking is something they actually need.

- Week 2: Build the smallest possible test. Maybe a landing page. Maybe manual matchmaking via email. Something that tests the core assumption without writing production code.

- Week 3: Get it in front of people. Watch what they do. Listen to what they say. Learn if the spark exists.

The code can wait. The assumptions can’t.

This post is part of a series reflecting on 26 years building tech companies—the failures, pivots, and lessons that shaped how I think about startups, product, and markets.